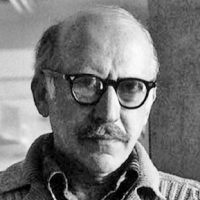

Saul Steinberg (1914-1999) was one of America’s most beloved artists, renowned for the covers and drawings that appeared in The New Yorker for nearly six decades and for the drawings, paintings, prints, collages, and sculptures exhibited internationally in galleries and museums. Steinberg’s art, equally at home on magazine pages and gallery walls, cannot be confined to a single category or movement. He was a modernist without portfolio, constantly crossing boundaries into uncharted visual territory. In View of the World from 9th Avenue, his famous 1976 New Yorker cover, a map delineates not real space but the mental geography of Manhattanites. In other Steinbergian transitions, fingerprints become mug shots or landscapes; graph or ledger paper doubles as the facade of an office building; words, numbers, and punctuation marks come to life as messengers of doubt, fear, or exuberance; sheet music lines glide into violin strings, record grooves, the grain of a wood table, and the smile of a cat.

Through such shifts of meaning from one passage to the next, Steinberg’s line comments on its own transformative nature. In a deceptively simple 1948 drawing, an artist (Steinberg himself) traces a large spiral. But as the spiral moves downward, it metamorphoses into a left foot, then a right foot, then the profile of a body, until finally reaching the hand holding the pen that draws the line.

This emblem of a draftsman in the act of generating himself and his line epitomizes a fundamental principle of Saul Steinberg’s work: his art is about the ways artists make art. Steinberg did not represent what he saw; rather, he depicted people, places, and even numbers or words in styles borrowed from other art, high and low, past and present. In his pictorial imagination, the very artifice of style, of images already processed through art, became the means to explore social and political systems, human foibles, geography, architecture, language and, of course, art itself.

Saul Steinberg was born in Romania in 1914. In 1933, after a year studying philosophy at the University of Bucharest, he enrolled in the Politecnico in Milan as an architecture student, graduating in 1940. The precision of architectural drafting taught him the potential of a spare two-dimensional line to describe a complex three-dimensional form. During the 1930s, Steinberg applied this lesson to the cartoons he began publishing in Milan for the twice-weekly satirical magazine Bertoldo. The incisive wit of these images would distinguish much of his art, long after he abandoned the strict cartoon format. By 1940, Steinberg’s drawings were appearing in Life magazine and Harper’s Bazaar. The following year, anti-Jewish racial laws in Fascist Italy forced him to flee. While in Santo Domingo in 1941 awaiting a US visa, he started publishing regularly in The New Yorker.

Steinberg’s association with The New Yorker continued for almost sixty years, resulting in nearly 90 covers and more than 1,200 drawings that elevate the language of popular graphics to the realm of fine art (many of these images are now available on www.cartoonbank.com). His career in the art world kept pace with his work for The New Yorker and other magazines. Steinberg’s first one-artist exhibition was held in 1943 at the Wakefield Gallery, New York. Three years later, he was among the “Fourteen Americans” in a landmark show at The Museum of Modern Art, his works exhibited alongside those of Arshile Gorky, Isamu Noguchi, and Robert Motherwell. Three major New York galleries have represented Steinberg, beginning with Betty Parsons and Sidney Janis and, since 1982, PaceWildenstein (www.pacewildenstein.com). To date, more than eighty solo shows of his art have been mounted in galleries and museums throughout America and Europe, including a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art (1978) and another at IVAM, the Institute for Modern Art in Valencia, Spain (2002). In 2006, “Steinberg: Illuminations,” the first comprehensive look at his career, set off on an eight-stop tour of the US and Europe. A traveling ambassador for American postwar art, Steinberg created one section of the Children’s Labyrinth mural at the 1954 Milan Triennial and a panoramic collage entitled The Americans for the US Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. At the Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1966, he collaged the walls with Le Masque.

The works in Le Masque evolved from Steinberg’s famous “masks”: brown-paper cut-outs or paper bags on which he drew all manner of faces to disguise himself and his friends, and then had the motley characters photographed by Inge Morath, alone or in groups, in a variety of interior and outdoor settings (www.ingemorath.org). The idea of disguise is central to Steinberg’s art. In the world as he saw it, everyone wears a mask, whether real or metaphorical. People invent personas through clothing, hairstyles, furniture, and posture; cities define themselves by their architecture, nations by their icons.

Steinberg likened these masquerades to the stylistic mannerisms of art. A style, after all, whether Cubism or Madison Avenue advertising, Pop Art or primitivism, converts reality into pictorial artifice. The use of style to lay bare cultural fictions pervades Steinberg’s work. Majestic Art Deco mountains loom behind the plain rendering of a small Wyoming town, revealing the grandiloquent self-image of the American West. In Georgetown Cuisine, style sends an enigmatic message about the circumscribed concerns of suburban wives: on a magazine reproduction of five women opening boxes (probably an advertisement for kitchenware); Steinberg drew over the faces in a cartoon style and turned the object of their attention into a primitivistic sculpture. The battle of the sexes becomes a graphic stand-off between male-speak geometry and feminine Art Nouveau flourishes. Steinberg appropriated the bold letters of billboards in an untitled work of 1971, but misnamed the colors in the words “BLUE” and “RED,” “YELLOW” and “GREEN” to signal the duplicitous address of advertising promotions. Paris is reduced to the flowery curves of an Art Nouveau Métro station and triangular-plan buildings that mark out wishfully broadened and empty vistas. With no cars in sight and pedestrians confined to the sidewalks, Steinberg’s Paris emerges as an idealized city seen through its urban architectural styles. Style and content are coincident in Las Vegas, crayoned in a casino’s garish hues and frenetic barrage of forms. The gambling woman, nearly all head and pocketbook, hits the jackpot at a slot machine. Her prize, however, is not money or chips but geometric shapes, while the symbols on the machine are as juvenile as the dream of instant riches. The multiplicity of graphic styles can also carry meaning, as in Canal Street, where the congestion of one of New York’s busiest thoroughfares becomes a congestion of linear modes–scribbled cars and stick-figure crowds flanked by spiky, pseudo-Cubist architectural implosions; in the background, a pair of ominous, heavily cross-hatched skyscrapers close off the street.

In another work, a 1964 drawing of a living room populated by different graphic motifs, Steinberg himself described the expressive potential of found styles. The drawing depicts “a conversation between people….A very hard outside with a soft inside sits on a straight-backed chair talking to a fuzzy spiral. On the sofa there is a boring labyrinth speaking to a hysterical line, a giggling, jittery bit of calligraphy. Then there is a dialogue between concentric circles and a spiral. The concentric circles represent the frozen, prudent people, the porcupine and turtle people. The spiral can look like a series of concentric circles….But actually the essence of spirals is different from the essence of concentric circles.”

Steinberg worked in a wide range of media, often packing several into a single image. Traditional media abound–ink, pencil, charcoal, crayon, watercolor, oil, and gouache–as do novel devices. He designed rubber stamps of people, birds, horsemen, and crocodiles, imprinting his compositions with their reiterative forms as well as with official-looking but purposely unreadable rubber-stamp seals. In Steinberg’s art, handwriting takes on the character of a drawing medium: he invented an elegant, but again unreadable, calligraphy with which he manufactured “documents”–fake certificates, diplomas, passports, and licenses whose illegibility deprives officialdom of its self-proclaimed authority. Although he primarily drew on paper, Steinberg also turned photographs into drawing surfaces, inking wheels below a shot of a bread loaf and, above it, a horizon dotted with houses and a gas station: a baked car speeding down an American highway. In the early 1950s, he drew on objects or entire rooms and had a photographer document the results, as in the empty bathroom whose tub he filled with a lounging woman.

It is not surprising that Steinberg’s first forays into sculpture were three-dimensional comments on the draftsman’s work. The wood Drawing Tables of the 1970s comprise arrangements of hand-carved, eye-fooling simulations of pens, pencils, brushes, rulers, sketchbooks, and seals. And if drawing tables and their implements can be carved, they can also be drawn. The pristine ink and pencil abstraction of 1969 with an artist (right) seated at a drawing table is not about the Cubism it emulates. Cubism, Steinberg tells us, is just one of many styles in which you can draw–and through which you can think.

Steinberg defined drawing as “a way of reasoning on paper,” and he remained committed to the act of drawing in an era dominated by large-scale painting and sculpture. Throughout his long career, he used drawing to think about the semantics of art, reconfiguring stylistic signs into a new language suited to the fabricated temper of modern life. He was, as the title of one of his books has it, the “inspector,” seeing through every false front, every pretense. Sometimes with affection, sometimes with irony, but always with virtuoso mastery, Saul Steinberg peeled back the carefully wrought masks of 20th-century civilization.