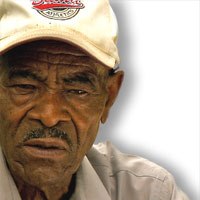

A folk artist who does paintings, assemblage and sculpture, Thornton Dial, Sr., known as Buck, spent his life in Alabama, where he married, had three sons and two daughters and lived in Bessemer. He was the “patriarch” of a clan of noted folk artists including his son, Thornton Dial Jr., known as “Little Buck”, and Richard Dial.

His art emanates from his concerns about racial and male/female relationships in America, with assemblages representing “what makes up the world as he sees it” (Rosenak, 102) and expresses his feelings about conflict and harmony and the importance of community. His work reflects his special concern about the struggle of blacks in white-dominated society.

Of his expression, he says: “I make art that ain’t spaking against nobody or for nobody neither. Sometimes it be about what is wrong in life. I do that because I want the world to be right. . . .It don’t make the world right just because I want it right.” (Riggs, 149)

He uses oil and water base paint and bold colors for his paintings and makes his sculptures from found objects and easily acquired materials such as tin, tree roots, bottles, carpet and plastic. Many of his pieces are large, often four feet square or more.

Dial Sr. held many jobs including carpenter, house painter, cement mixer and iron worker. From 1952 to 1980, he worked for the Pullman Standard Company, which manufactured railroad cars in Bessemer. After retirement from that job, when not pursuing his art interests, he raised turkeys and made wrought-iron lawn furniture with his sons.

From the time he was young, according to him, he “was always making ideas, but the notion that they were art never occurred to me until I met Bill Arnett” in 1987. Arnett was an art dealer from Atlanta and was especially interested in folk art. Arnett promoted his art and arranged an exhibit of Dial’s work in 1988 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and in 1989 at the Latin American Gallery in New York City.

Source:

Chuck and Jan Rosenak, Museum of American Folk Art Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists, p. 102

Thomas Riggs, Editor, St. James Guide to Black Artists, p. 149